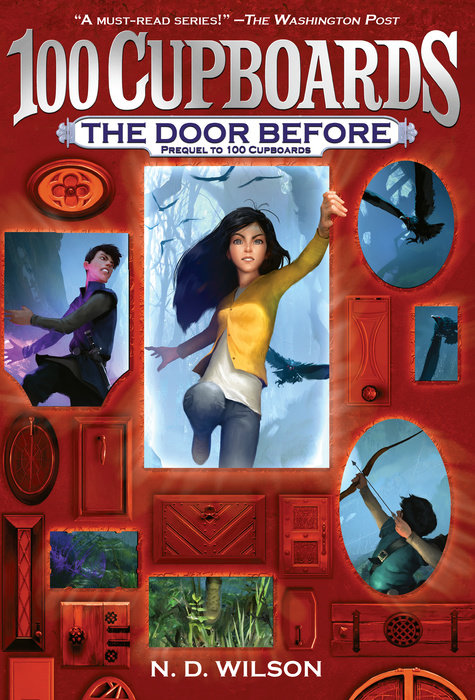

The Door Before (100 Cupboards Prequel)

The Door Before (100 Cupboards Prequel) is a part of the The 100 Cupboards collection.

Open the cupboard door to this action-packed fantasy that will take readers to the very beginning of the bestselling 100 Cupboards series!

100 Cupboards, 100 Worlds of Adventure!

When Hyacinth finds an unusual door, two boys in search of vengeance, and a witch intent on destroying the world, the ultimate battle of good vs. evil begins!

Hyacinth Smith can see things that others miss, stop attack dogs from attacking, and grow trees where no trees have grown before. But she’s never had a real home. When her father tells them they’ve inherited a house from their great-aunt, Hyacinth sees trouble brewing. Their great-aunt has been playing with forces beyond her control, using her lightning-tree forest to create doors to other worlds. When one door opens, two boys tumble through . . . bringing with them a battle with the undying witch-queen, Nimiane. Hyacinth, together with the boys, must use her newfound magic and all of her courage to journey straight into the witch’s kingdom in a daring plan to trap evil and kill the immortal.

“A must-read series!” —The Washington Post

“[100 Cupboards] is my favorite kind of fantasy.” —Tamora Pierce, #1 New York Times bestselling author

"This fast-paced fantasy features empathetic heroes." —School Library Journal

An Excerpt fromThe Door Before (100 Cupboards Prequel)

One

Every storm will spill a final drop. Every mortal will draw a final breath. Every road will carry a final traveler.

High on a towering cliff of sandstone, above a gray churning sea and below swaying groves of redwood trees, all three of those finales were coming to pass in the same place and in the same dusky twilight.

While hungry waves watched, a coal-colored truck with only one headlight crawled along the cliff’s lip, tugging a stubby silver camper behind it, windows gleaming wet.

For more than a century, the crude cliff road had carried its travelers safely through gullies and over rises, well back from where the continent ended and the Pacific Ocean began. But there is nothing in the world so greedy and determined as the sea. Meadows of wildflowers and stands of cedars had all been chewed away, leaving nothing to border the road but air and floating gulls and drifting spray from the largest waves.

The road’s final traveler was a twelve-year-old girl in the camper trailer, seated on a defeated old cushion on a little bench in the very back, beside a fold-up table covered with loose playing cards. She was Hyacinth Maxine Smith, and her eyes were on the western horizon, where the faint white glow of the sun was just vanishing. Her left hand propped up her chin, and her right was rubbing her little brother Lawrence’s blond buzzed head as he snoozed in her lap.

Hyacinth was the final traveler only because her four siblings were farther forward in the trailer, even if only slightly. Daniel was in a flannel sleeping bag, snoring on the narrow slice of floor. His wide, angular, sixteen-year-old shoulders had grown wider and more angular in recent months. His hair was darker and even shorter than Lawrence’s. Harriet was humming on the trailer’s fraying sofa with her legs curled beneath her. She was fourteen, her sunny brown hair was always in a thick braid that almost always ended up in her mouth, and her eyes were like sandy blue tide pools, sometimes cloudy, sometimes clear. Harriet was the storyteller, the singer, and the second mother. Even though she was younger than Daniel, she had appointed herself Lord High Chaperone. When parents were absent, what Harriet said almost always stood.

Circe was asleep on Harriet’s shoulder. Her eyes were golden brown, her pearly blond hair was chopped in a sharp line above her jaw, her laugh was quick and never quiet, and she could only keep serious when she was sleeping.

Hyacinth may have only been a year and a half younger, but Circe’s quick confidence made her feel incredibly small. Adults talked to Circe like an equal, and to Harriet like a superior. Both of the older girls were tall, bright, and unafraid. Like Daniel. Even Lawrence. While in any group, small or large, Hyacinth slipped to the back. She, the smallest Smith sister, the girl with the midnight hair and cool eyes, watched. She studied. She felt. She wondered. She noticed. But she rarely said what she had noticed, because she quickly doubted her own perception and made herself less sure than she was. Unless her sunny sisters dragged it out of her . . . and agreed.

Lawrence, only eight, writhed and grunted, then sat up, blinking. “Hy?”

“You’re okay,” Hyacinth said. “Go back to sleep.”

Lawrence crossed his arms over the loose playing cards on the table and flopped his head forward.

A single fat drop spattered against the window, and Hyacinth watched its ruins run in a web across the glass.

She didn’t know that she was watching the storm’s final drop.

She didn’t know why her parents were keeping a big man tied up under a tarp in the back of the truck. And she didn’t know that he had just kicked, shuddered, and taken his final breath.

As he exhaled, the ground shook.

The trailer suddenly bounced and slid toward the cliff, and the truck veered and accelerated, throwing tails of gravel, jerking the trailer hard inland, and the trailer skittered and swung and she fell backward and Lawrence yelled and the playing cards flew and Daniel and his sleeping bag slid toward her and Harriet and Circe both screamed and fell off the sofa onto Daniel’s head. Half a mile of cliff was falling into the sea behind them. The roar muted the engine and silenced the wind and shook the very world. The truck and trailer roller-coastered up through walls of brush and slid through mud and stopped in a bed of drowning ferns beneath a massive old ten-trunked cedar with gnarled roots that looked strong enough to hold the earth together. Breathing hard, with her heartbeat thundering in her eardrums, Hyacinth rose to her knees on her cushion and peered out the rear window and saw the ruin and the wreckage of the coast and muddy waves romping over fresh stone and a whole forest of heavy timber being dragged out to sea.

She knew she had been the road’s final traveler. Death had come close, and it made her feel cold to her core.

Harriet and Circe stood behind her.

Daniel kicked his way out of his sleeping bag and hopped up. Together the siblings watched the ocean jump the rubble and test the new cliff with shattered spray.

“Everyone alive?” Harriet asked.

“I am,” Lawrence said. He was wide awake and bouncing. “I’m alive. Can we get out and look? I want to climb.”

“No,” Harriet said. “No way.” She pushed her braid back and turned to the front of the trailer. “I hope we aren’t stuck. I so wanted a real bed tonight.”

“We almost died,” Daniel said. “Be grateful for any bed that isn’t at the bottom of that cliff.”

“And a shower,” Harriet added. “Badly need. At least if I’m going to feel human again.”

The door to the trailer banged open and Trudie Smith leaned inside, quickly scanning all five of her children with worried eyes. She, like Hyacinth, had dark hair and eyes like the moon in winter. Her hair was in a tight ballerina bun, and her skin was creased from wind and sun and work and worry.

“All present and accounted for?” she asked. “Anyone bleeding?”

“Yes ma’am! No ma’am!” Lawrence bounced up and down on the seat next to Hyacinth.

“That was interesting,” Circe said. She shook back her short hair, more excited than scared. “It came out of nowhere. Was it an earthquake?”

“No. Just a lot of rain,” Trudie said. “And then a truck pulling a trailer.”

“You really think we were heavy enough to do that?” Daniel asked, but his mother was already retreating through the door.

“Sit down and grab on to something,” she said. “This will be a rodeo for a bit.”

The door banged shut and Lawrence slammed into Hyacinth, laughing, grabbing on to her arm. Hyacinth winced but didn’t push her brother away.

“I don’t know how one truck and trailer could knock that much cliff into the ocean,” Harriet said. “Did you see all those trees?”

“We almost died,” Circe said. “So what if it was the rain or the truck or an earthquake? My heart is still jumping.”

Hyacinth opened her mouth to speak and then shut it again quickly. A thought had darted through her mind. But it was childish. Not something she wanted to share.

Harriet and Circe both looked at her. Harriet brushed her braid against her lips. Circe leaned forward.

“What is it, Hy?” Circe asked.

The truck engine roared and mud and gravel rattled against the windows as the trailer lurched forward.

Hyacinth looked out her window, watching brush and leaves scrape across the glass.

“Hy!” Lawrence nudged her firmly with his elbow. “What is it?”

“I was just thinking,” Hyacinth said quietly. This was how it always went. They made her talk in the end, so she may as well say it now. “I was just thinking about the man in the truck. He might be why the cliff fell. We all know he isn’t normal. Not by a long shot. Not like anyone else Dad has ever tracked.” She looked at her older siblings. “Maybe. That’s what I was thinking, anyway. I’m sure it was just the rain.”

But she wasn’t sure. And neither was anyone else.

“It’s not like Dad is always tracking people,” Circe said. “That makes him sound strange.”

“He is strange.” Daniel’s voice was low. “We all are. And he’s tracked enough. Whenever the Order needs help.”

“I remember a few,” Harriet said. “And all of them were . . . wild.”

“Powerful,” said Hyacinth. “Not just wild.”

The trailer squeaked and bounced. Heads swayed with the motion.

Lawrence brushed the last loose cards off the table onto the floor and then stared at them. “But how could that man knock the cliff down?” he asked. “Dad shot him. And he burned his belt and his hair and tied both of his mouths shut.”

“Yeah,” Hyacinth said. “I know he did. We were just talking.”

Two months prior and hundreds of miles away, Hyacinth’s father had made an announcement at the dinner table. It was the same announcement Albert Smith had made to his children many times before at many different dinner tables. The Smith family was moving. The people who actually owned the house where they had been living would be returning soon. Albert had received a call or a letter or a telegram and another house was waiting for them, or one would be soon. There would be more overgrown gardens for the children and their mother to attack. There would be more lonely animals desperate for attention and training. More horses for Hyacinth to groom. More dogs for Lawrence to play with and Hyacinth to train. More engines for Daniel and his father to repair--trucks, motorcycles, boats, airplanes, and even one strange little jungle train with tracks to clear and a bridge to replace.

Hyacinth Smith had lived in wide-open villas with fountains and pools lined with hand-painted tiles as bright as the parrots in the trees. She had lived on desert ranches with one thousand longhorns, and in mountain lodges where the snow piled up ten feet deep. She had lived on the sand beside the Atlantic and on an island in the Gulf of Mexico. The Smiths had cared for run-down camps beside glacier lakes, had tracked down and recovered missing swamp mansions, and had tended huge houses in cities where no one spoke English. Hyacinth had lived like a princess and like a pioneer. She had slept on silk sheets and on piles of straw and on bunk beds with shrieking springs. She had studied the dolls and decorations of dozens of different girls, the family photos, the books, and she had wondered what it would be like to have a place of her own. A place where some other girl could stay and never quite belong.

Hyacinth could be comfortable almost anywhere, but she felt like she belonged nowhere.

The last house had been in the New Mexico mountains with stables bigger than any she had ever seen and a river rock fireplace large enough to hold a pitched tent. The horses had been well cared for, the dogs well trained, the house well cleaned, the gardens sparse but healthy. The job had been all for her father--two airplane repairs and one rebuild. So Hyacinth and her sisters had been able to read and write and dream and talk and laugh as the sun set in the evenings, and catch up on some of the studies their mother had planned for them.

And then a letter for Albert Smith--the first Hyacinth had ever seen carried by a pigeon.

And then the dinner table announcement.

And then goodbye to the horses and the landscape and the house and the gardens, and hello to the cramped trailer and the slow wander to somewhere else.

But this time was different. This time Albert hadn’t even finished his job first. Not even close. Lawrence had bounced around clamoring for information on where they would be living next, wondering if the owner had sons, and if so, what age, and oh, would there be dogs?

“Two sons,” Albert had said. “Eight and sixteen. Three daughters.” He had crossed his arms and looked at his wife. “Gertrude, you remember the girls’ ages?”

“I do.” Trudie had smiled. “I ought to. Those three made their birthdays easy to remember.”

“Wait a minute . . .” Harriet scrunched her brows.

“You’re talking about us?” Circe asked.

“That’s right,” their father said. “Our place. Our very own place in California. That’s where we’re living next.”

The girls had squealed and laughed in shock, and Daniel had grinned and picked up his still-smiling mother, and Lawrence had danced and made up a song about having a home and about never leaving ever not even when he was dead, but Hyacinth had known that there was more, and that it wasn’t all good. She had known from the set of her father’s jaw and the tension in his thick oil-stained fingers and the ring of hardness in his eyes that surrounded the happiness at their centers. She had known, but she had not said.

Hyacinth had looked carefully at her father, and he had understood and grabbed her tight and pulled her in under his arm and kissed the top of her head.

“Just one job first,” he had said. “Shouldn’t take more than a week or two. And then you get your own plants and your own dirt and your own little room and a shelf for your own books. Smile, Hy. Smile.”

And she had.

Until the wanderings in Mexico. And the ghost towns in the California mountains. And the bodies. And then one night, Albert and Trudie had left the kids alone with the camper beside an icy river. And in the morning, they had returned.

An unconscious man with two mouths was bound and gagged in the back of the truck. He had been shaved, and his hair burned, and his black fur belt had been burned too, in case it had been charmed. And the kids had watched from inside the camper and the flames had jumped high and white and thunder had shaken the windows.

Albert, smiling, almost limp with relief, had told his children that it was time. Time for a home. Time for a place that would be theirs forever.

Hyacinth hadn’t believed him.

Oil-stained hands with stubbed nails and cracked knuckles lifted Hyacinth easily up off the floor. Her head draped over a broad shoulder, her arms swung limply at her sides, and her dreaming mind began to return to reality.

Her father was carrying her. The trailer door was open and he ducked carefully out into cool night air.

The sky was clear and the moon was high. Hyacinth could hear the ocean.